In May I was privileged to attend the Harvard Kennedy School’s executive program The Art and Practice of Leadership Development, and learn both from the Faculty (led by the incredible Professor Ronald Heifetz) and a cohort of leaders from around the world.

Many people have asked me what I learned, which I have been struggling to articulate and document. Okay… here goes… Five key lessons with two caveats: A) My lessons are changing with reflection and implementation time, and B) I have chosen to highlight lessons here that I can articulate in a paragraph or two.

Warning – This post well exceeds my usual self-imposed 350-word limit!

Leadership is about motivating people to resolve adaptive challenges, and often requires taking them to the ‘frontier of their competence’. It’s not easy. We can expect people will push back, and when they do our job is to pace the change so they can absorb it.

‘Leadership is the work of distributing loss at a rate people can tolerate.’ A significant factor in how effective you will be in facilitating a successful outcome is your level of self-awareness and your ability to understand others.

1) Leadership is about mobilization. Adaptive leadership provided a new definition for me: To lead is to mobilize others on behalf of the collective, engaging them in both resolving a challenge, and in the necessary learning and innovation.

I like this definition although I am still thinking through how it fits with my pre-existing ideas. As Prof Heifetz says, truly listening to someone else is risky business because you may need to change your mind!

Who could you to mobilize to resolve the challenge?

2) Many of the tricky leadership issues we face are Adaptive Challenges. Technical problems, while they may be far reaching and complex, have known solutions if we spend enough money and time, and get the right people (typically experts) together.

Adaptive Challenges don’t have a known solution – and oftentimes, even the problem is not clear. We can’t anticipate the response when we begin to implement an intervention. Even with constant review and course correction, we may not land at the expected end point. Adaptive challenges usually involve multiple stakeholders, and are often risky to address. Consequently we tend to either ignore them, or attempt to treat them as technical problems – with little or no success.

For success, it’s necessary to develop new capacities.

Are you facing technical problems? Or adaptive challenges? Who do you need to involve in the response? What new capabilities are needed?

3) Learning requires operating at the frontier of our competence. In the opening session, Prof Heifetz gave us ‘permission to be confused’. In hindsight I wonder if this was really an instruction and not permission! Heifitz stressed that learning happens at the ‘frontier of our competence’.

Most people will do whatever we can to get out of confusion… As quickly as possible… Heifetz has a strong view that ‘People only resist change when they think it will come at a loss for them’.

How could you promote learning – for yourself, your team and your community – by having the courage to stay in the discomfort of confusion so you can gain new insight?

4) Facilitation that puts the work back where it belongs is an art form. Every member of the Faculty displayed the most astonishing facilitation I have ever experienced. Astonishing because while it looked very ‘light touch’ and highly responsive to the energy of the group, it was managed within a boundary that provided maximal learning.

Faculty members held the space for us to work through stuff (my term!) that at times was complex, highly emotional, and fraught with often unidentified undercurrents. They were actively present and yet hands off, resisting the temptation to step in and rescue or provide answers, and encouraging us to let others find their own learning. This was summarised as ‘putting the work back where it belongs’.

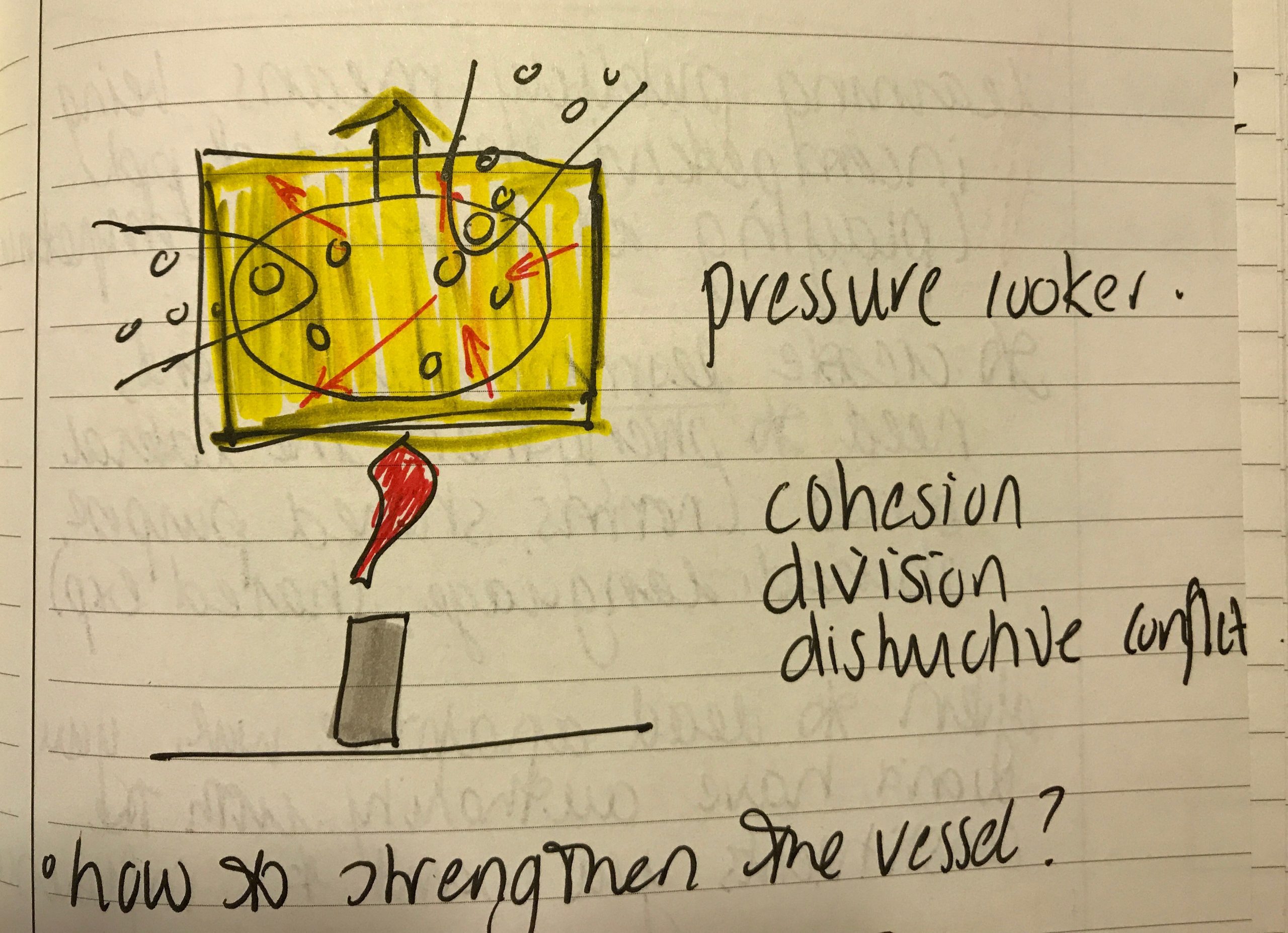

They used the metaphor of a pressure cooker – insufficient pressure and the meal does not cook, while too much pressure leaves the food soggy and falling apart. Or worse still, the cooker explodes all over the kitchen.

This was especially fascinating for me because this is the way I like to facilitate… But this was my facilitation style on steroids and I now have a new standard of ‘learning discomfort’ to aspire to.

As a leader, where are you doing the ‘work’ that is not yours to do? What control do you need to release so that people can develop insight and solutions they are ready to own?

5) We rarely travel alone. While we think we represent our own views, we rarely do. Instead we have a whole truckload of constituents in our shadows or on our shoulders, each of whom has strong views which they hope we will honour. These constituents include our own professional selves, people in our social and familial networks, and our ancestors who are no longer with us.

We were encouraged to consider the question ‘who would you be disappointing, if you do / don’t do this?’ For example, perhaps by saying ‘yes’, I would be letting down the values I hold as a ‘coach’… Or maybe my husband might not support that direction … Or perhaps my grandfather had strong views on this subject, and I wouldn’t want to let him down….

To add to the complexity, everyone else involved in the conversation also has their own hidden stakeholders too, so don’t be fooled into thinking there is only two of you in the conversation!

Next time you hear yourself saying ‘I should xxx’, ask yourself ‘who would I be disappointing, if I did / didn’t do this?’

These are my 5 key learnings and so so so much more! Would I recommend the program and the experience? Yes!

PS If you read this, nod your head, and think you have it covered, I will leave you with bonus throw away from Ron Heifetz: ‘Most people can’t learn as fast as they think they can.’

Go fearlessly.

STAY IN THE LOOP